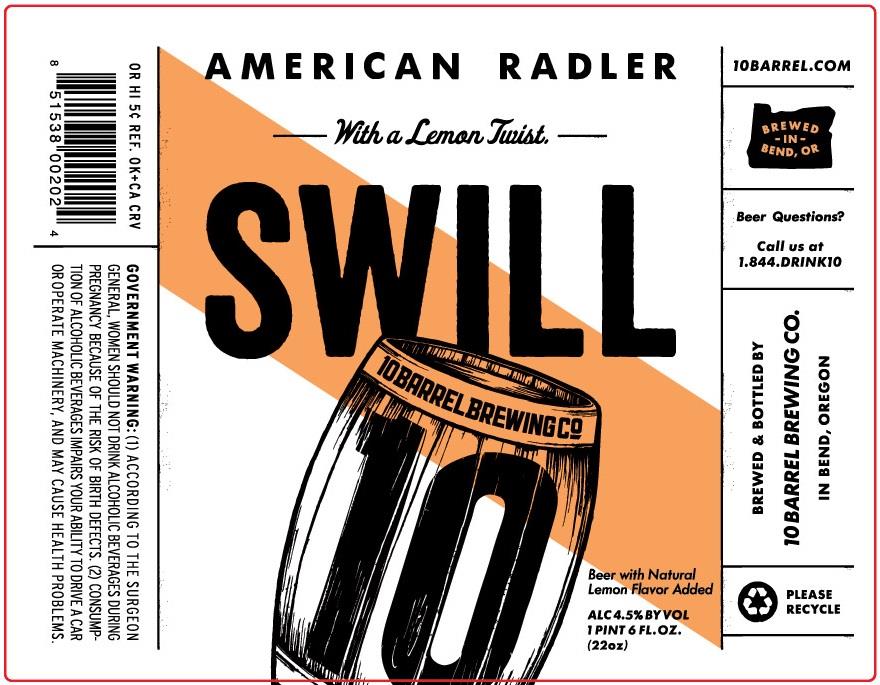

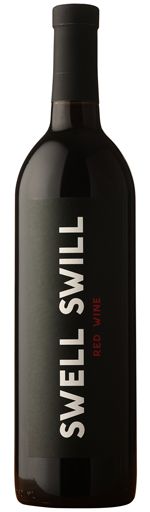

A recent application before the United States Patent and Trademark Office, 10 Barrel Brewing, LLC sought to register the mark SWILL (in standard characters) for beer in International Class 32 (for beer) on the Principal Register. See In re 10 Barrel Bxrewing, LLC, Serial No. 86190248 (May 31, 2016) [not precedential]. The application for registration was originally refused by the Examining Attorney under Section 2(d) of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1052(d), on the ground that Applicant’s mark resembled the mark SWELL SWILL in standard characters, previously registered for wine in International Class 33, and was likely to cause confusion. Applicant appealed to the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (after the refusal was finalized) and requested reconsideration.

The Board first addressed the comparison of the marks with respect to the du Pont factors for likelihood of confusion, which focused on the similarity or dissimilarity of the marks with respect to their appearance, sound, connotation, and commercial impression. The Board’s analysis was based on the entirety of the marks, not specific components or marks, but also recognized that a particular feature may be given more or less weight as long as the ultimate conclusion is based on the consideration of the marks in their entireties. When comparing the marks (Swill and Swell Swill), the Board noted that Applicant “merely deleted the term SWELL from its mark.” Id. at 3. The Examining Attorney had submitted evidence that the term Swell was a weak indicator of the source of the goods, which the Board took to understand that Swell has a lower impact with respect to overall commercial impression, thus indicating that Swill had a stronger impact. Id. at 4.

Applicant argued that the confusion between the Applicant’s Mark SWILL and registrant’s mark SWELL SWILL was unlikely due to the juxtaposition between the terms “swell” and “swill,” which Applicant argued developed incongruity and integrated alliteration that, when viewed together, created a commercial impression that is disparate and dissimilar from the Applicant’s Mark SWILL. Id. Applicant submitted a copy of a dictionary definition indicating that “swill” means “liquor or other alcohol of poor quality” and maintained that such incongruity was further evidenced by the lack of disclaimer of the descriptive term “swell” in the cited mark. Id. Applicant further argued that the effect of the incongruity is that none of the arts if the mark was actually dominant; instead, only parts of the mark acted together to produce an implication that is “greater, and different, than the meaning of any individual part.” Id.

Unfortunately, the Board was not persuaded by Applicant’s firm arguments. The Board reasoned that while “swell” and “swill” may be incongruous, “there is a very similar connotation in Applicant’s mark to extent that both marks are characterizing their goods in a self-deprecating manner.” Id. at 4–5. The Board noted that consumers are likely to perceive the use of “swill” sarcastically or in jest and would “not believe that either entity would sincerely suggest that their goods are poor quality. The irony that an entity would identify its own beverage as ‘swill’ is present in both marks.” Id. at 5. Further, the use of “Swell” in Registrant’s mark can be understood as an emphasis of the satirical suggestion that Registrant’s wine is “swill” or of poor quality. Id. In conclusion, any incongruity that exists between SWELL and SWILL does not detract from the marks’ overall similar connotation or commercial impressions. Id.

Applicant further argued that the term “swill” is weak, provided a list of third-party registrations containing the term “Swill,” and that the cited mark should not be afford a broad scope of protection. The Board also rejected this argument, noting that the weakness of a particular mark is generally determined within the context of the number and nature of similar marks in use in the mark with respect to similar goods or services. The Applicant’s submission of third-party registrations was given little weight because such registrations did not establish that the mark is actually used on a commercial scale in the marketplace or that consumers are used to seeing it. Id. at 6.

Applicant further argued that the term “swill” is weak, provided a list of third-party registrations containing the term “Swill,” and that the cited mark should not be afford a broad scope of protection. The Board also rejected this argument, noting that the weakness of a particular mark is generally determined within the context of the number and nature of similar marks in use in the mark with respect to similar goods or services. The Applicant’s submission of third-party registrations was given little weight because such registrations did not establish that the mark is actually used on a commercial scale in the marketplace or that consumers are used to seeing it. Id. at 6.

Thus, the Board determined that because Applicant’s mark and Registrant’s mark are similar in connotation and commercial impression, and because they share a common term SWILL, consumers are likely to view Applicant’s SWILL mark as a variation of Registrant’s SWELL SWILL mark. Thus, the Board found that Applicant’s mark was highly similar to the cited mark. The first du Pont factor supported a finding that confusion was likely.

Next, the Board went on to compare the goods, trade channels, and consumers. The issue is not whether purchasers would confuse the goods, but rather whether there is a likelihood of confusion as to the source of the goods. Id. at 8. Examining Attorney submitted a plethora of use-based third-party registrations that sought to prove the goods were related and, in some instances, showed that the same entity had registered the same mark for “beer” and “wine.” The Board reasoned that the registrations had some probative value should they suggest the goods are of a kind which may stem from a single source under a single mark. Id. The Examining Attorney also submitted Internet evidence indicating that there are third-parties who produce and offer both beer and wine for sale under the same mark, which the Board took to be further proof that consumers may expect to find both Applicant’s and Registrant’s goods as coming from a common source and thus closely related. As a result, the Board found that the second du Pont factor also weighed in favor of finding a likelihood of confusion. Id. at 9.

The Board went on to examine the channels of trade (the third du Pont factor), and noted that it would presume the goods would travel in all channels of trade appropriate for such goods and to all usual customers of them since there were no restrictions on channels of trade on either application. Id. After a brief discussion about liquor store purchasing, the Board found in favor of the third du Pont factor.

Finally, the Board reviewed the fourth du Pont factor (conditions under which buyers and to whom sales are made). Applicant argued that purchasers of the types of good identified in its application are very sophisticated and are not impulse buyers. The Board reasoned that, while some purchasers of Applicant’s and Registrant’s goods may certainly be educated and sophisticated with respect to their purchases and exercise degree of care, such did not mean that all purchasers exhibit the same qualities. Further, because the items may be inexpensive and purchased by the public at large, it must be assumed that purchasers include casual consumers. As a result, it did not mean that such purchasers are sophisticated and knowledgeable about alcohol beverages or in the field of trademarks or immune from source confusion. Id. at 10.

Based on all the above, the Board found that Applicant’s mark, as used in connection with the identified goods, resembled Registrant’s mark as to be likely to cause confusion or mistake or to deceive under Section 2(d) of the Trademark Act. Thus, the refusal to register Applicant’s mark for SWILL was affirmed.

For more information on wine or alcohol law, or trademark, please contact Lindsey Zahn.

DISCLAIMER: This blog post is for general information purposes only, is not intended to constitute legal advice, and no attorney-client relationship results. Please consult your own attorney for legal advice.