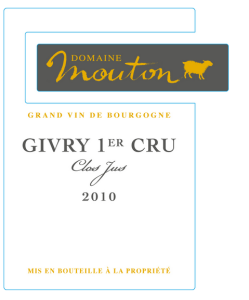

Bordeaux estate Château Mouton Rothschild recently sent a Burgundy wine producer, Vintner Laurent Mouton, a cease and desist letter, asking the producer to stop use of the name “Domaine Mouton” on its wine labels. The Château claimed that use of such a name on wine labels was “unauthorised reproduction [and] amounts to counterfeiting of pre-existing brands belonging to Rothschild companies.” See Change the Name of Your Wine, Rothschild’s Chateau Tells Burgundy Wine House. The Château believes that wine drinkers may mistake the Domaine Mouton labels for being related to Rothschild’s Chateau Mouton Rothschild or Mouton Cadet brands. In addition, the Château argues that Domaine Mouton’s labels display a “clearly parasitic” attempt to reap the benefits of “the great Mouton’s coattails.” Id. Château Rothschild is asking Domaine Mouton for 410,000 Euros in damages and interest over the course of three years. See id.

Bordeaux estate Château Mouton Rothschild recently sent a Burgundy wine producer, Vintner Laurent Mouton, a cease and desist letter, asking the producer to stop use of the name “Domaine Mouton” on its wine labels. The Château claimed that use of such a name on wine labels was “unauthorised reproduction [and] amounts to counterfeiting of pre-existing brands belonging to Rothschild companies.” See Change the Name of Your Wine, Rothschild’s Chateau Tells Burgundy Wine House. The Château believes that wine drinkers may mistake the Domaine Mouton labels for being related to Rothschild’s Chateau Mouton Rothschild or Mouton Cadet brands. In addition, the Château argues that Domaine Mouton’s labels display a “clearly parasitic” attempt to reap the benefits of “the great Mouton’s coattails.” Id. Château Rothschild is asking Domaine Mouton for 410,000 Euros in damages and interest over the course of three years. See id.

Laurent Mouton and his family own thirty acres of vineyard land in Givry and produce roughly 60,000 bottles of Pinot Noir and Chardonnay each year under the Domain Mouton label. See id. He is the fourth generation of his family to produce and bottle wine under the family’s name Mouton. Id. To the contrary, Château Mouton Rothschild owns 207 acres in the Pauillac appellation of Bordeaux and “produces 500,000 bottles per year of what is considered one of the world’s greatest clarets.” Id. Mr. Mouton declares that the amount of damages for which the Château is asking would likely bankrupt his company.

In an attempt to reconcile, Mr. Mouton offered to change his labels to read, “Domaine L. Mouton,” to which Château Rothschild has not responded. Further, the Burgundy producer believes that the Château’s concerns would be more reasonable if the two were both located within Bordeaux (or Burgundy) and offering their wines for around the same price points.

This particular dispute reminds me a lot of the recent and alleged suit on behalf of French Champagne maison Veuve Clicquot against a smaller Italian sparkling wine producer, Ciro Picariello. See Champagne House Veuve Clicquot Sues Italian Sparkling Wine Producer Over Label. In that case, the Champagne house sued a family-owned winery for use of a certain color on its sparkling wine labels. The Champagne house was supposedly concerned that the orange label of Ciro Picariello’s sparkling wine could cause consumer confusion with its Reims-based Champagne product, thus causing economic damage to Veuve Clicquot. Whereas, in that particular case, the concern was over a color as opposed to the name, the disagreements do present certain similarities. For example, both instances entail a legal measure against a smaller wine producer in a different region. In addition, both tales are pursued by powerful wine producers with immeasurable resources. (Note: At publication, it is unclear if a suit has been pursued on behalf of Veuve Clicquot; shortly after news erupted regarding an alleged lawsuit, the maison denied filing suit against the Italian producer and instead maintained that it had contacted Ciro Picariello to note the similarities of the labels, and to ask if there was a possibility Ciro Picariello’s labels could “evolve” to avoid any potential confusion between the two wine brands. See Veuve Clicquot Denies Lawsuit Over Label.)

But some differences do exist here. In this case, the issue at stake pertains to the wine’s name—not the color of the label. But this is not the first time the Château has pursued legal measures to protect its name. In 2012, the Baron Philppe de Rothschild group lost a legal battle against the New Zealand wine producer of the “Flying Mouton” label in which the French company alleged the New Zealand’s wine resembled its Mouton Cadet brand. Id. The New Zealand court reasoned that the use of the term “mouton,” which is French for sheep, may have derived from the vineyard’s prior use as a sheep farm. With the New Zealand court’s ruling in mind, it certainly seems that a family name for a vineyard should prevail especially considering that Domaine Mouton has been established for several generations. Further to the point, it is possible that the New Zealand court may have implied the Rothschild name (or the Mouton name when used in conjunction with the Rothschild name) holds greater significance than the Mouton name by itself. Irrespective, the above represents another instance where a larger wine power seeks to exert its resources over those of a smaller producer in an effort to purportedly protect its trade name.

Photo property of the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau.

DISCLAIMER: This blog post is not intended as legal advice, and no attorney-client relationship results. Please consult your own attorney for legal advice.

Very interesting post. I would like to clarify that in order to determine if there is a risk of consumer confusion European Union brand law does not consider relevant that (i) the wine producers are located in different wine regions, one in Bordeaux and the other one in Burgundy, and /or (ii) the brand owners offer their wines for very different price points or qualities (see Judgment of the General Court of the European Union, may 14, 2013, Case T 393/11).

Hi Jose:

Thank you for your comment and your insight — very helpful indeed to hear from an EU lawyer. Thank you also for the Judgment reference; certainly something relevant to look into more, especially with this case in mind.

The only people who benefit from this nonsense is attorneys. How many “Latour” names exist in Bordeaux? Twenty? Thirty. Had a similar issue with DRC some 30 years ago. The French just don’t have a sense of humor.