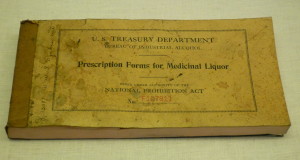

As lovers of wine and the law, we all know about the renowned 2005 Supreme Court case Granholm v. Heald, as well as several recent wine lawsuits from the early and mid-2000s involving our precious beverage. In the upcoming weeks, On Reserve seeks to focus on additional cases that shaped the legal world of wine as we know it today. Perhaps one of the least recognized wine cases of the early twentieth century stems from the Prohibition time period in America. During that time period, the Eighteenth Amendment prohibited the sale, manufacture, and transportation of intoxicating liquors for beverage purposes within the United States and its territories. See U.S. Const. amend. XVIII, § 1. The exact text of the amendment, by use of the phrase “for beverage purposes,” suggests that intoxicating liquors had a legal purpose aside from consumption, but the amendment fails to define such purposes in subsequent sections. The Volstead Act, the enabling legislation of the Eighteenth Amendment, carved out specific circumstances under which intoxicating liquors were permitted, which included sacramental and medicinal wines that received a license from the federal government. But what, exactly, were the non-beverage purposes for which intoxicating liquors could be used during the Prohibition time period? The Supreme Court case Dumbra v. United States, 268 U.S. 435 (1925), tackles this exact question.

As lovers of wine and the law, we all know about the renowned 2005 Supreme Court case Granholm v. Heald, as well as several recent wine lawsuits from the early and mid-2000s involving our precious beverage. In the upcoming weeks, On Reserve seeks to focus on additional cases that shaped the legal world of wine as we know it today. Perhaps one of the least recognized wine cases of the early twentieth century stems from the Prohibition time period in America. During that time period, the Eighteenth Amendment prohibited the sale, manufacture, and transportation of intoxicating liquors for beverage purposes within the United States and its territories. See U.S. Const. amend. XVIII, § 1. The exact text of the amendment, by use of the phrase “for beverage purposes,” suggests that intoxicating liquors had a legal purpose aside from consumption, but the amendment fails to define such purposes in subsequent sections. The Volstead Act, the enabling legislation of the Eighteenth Amendment, carved out specific circumstances under which intoxicating liquors were permitted, which included sacramental and medicinal wines that received a license from the federal government. But what, exactly, were the non-beverage purposes for which intoxicating liquors could be used during the Prohibition time period? The Supreme Court case Dumbra v. United States, 268 U.S. 435 (1925), tackles this exact question.

In 1925, a family known as the Dumbras operated their winery under the “sacramental and medicinal” exception to the national prohibition on intoxicatin liquors. The Dumbras operated two distinct businesses in adjoining buildings in New York City on East 16th Street: a grocery store and a winery. In the grocery store, the family sold traditional dry goods and produce; in the winery next door, the Dumbra family produced wine for sacramental purposes. The latter was done with the permission of the federal government (i.e., through a federal permit allowing the Dumbras to manufacture and sell wines for non-beverage purposes).

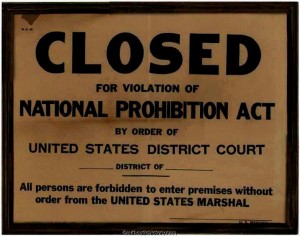

However, during the era of Prohibition, undercover agents visited the Dumbras’s grocery store pretending to be customers. The agents learned from an anonymous tip that any customer could buy wine from the grocery store for non-sacramental and non-medicinal purposes (i.e., for beverage purposes). The tip said the Dumbras’s store did not ask if the purchaser was using the liquor for non-beverage (or for beverage) purposes. Agents of the federal government obtained a search warrant and went through the properties of both the grocery store and the winery. The warrant allowed the seizure of any intoxicating liquor possessed at the Dumbras’s stores that was in violation of the National Prohibition Act. The agents seized a total of 74 bottles of wine from the grocery store and 50 barrels of wine from the winery. When the agents requested the warrant, however, it was not noted that the Dumbras in fact held a federal permit that allowed them to sell intoxicating liquors for medicinal or sacramental purposes.

The case made its way to the Supreme Court where the Dumbra family claimed that the actions of the agents were an unreasonable search and seizure without probable cause, thus in violation of the Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution, and sought to quash the search warrant. In totality, the Fourth Amendment reads:

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized. U.S. Const. amend. IV.

The Dumbras argued the warrant was issued erroneously because the Dumbra family held a federal permit allowing the family to produce and sell wine for non-beverage purposes. Additionally, the Dumbras argued that the search warrant was issued to an officer having no authority to receive and execute said warrant. The family asked the Court to quash the warrant for the seizure of the 50 barrels of wine from the winery.

With respect to the authority of the agent to execute the warrant, the Court rejected the Dumbras’s argument. The Court cited Steele v. United States, 267 U.S. 505, reasoning that Steele held that prohibition agents or employees of the United Sates have the power and authority to serve a search warrant with respect to provisions of the Espionage Act and the National Prohibition Act. As a result, the Court reasoned, the warrant for the Dumbras’s store was served by an agent who was authorized to execute said warrant.

The Court next discussed whether the affidavit upon which the search warrant was issued provided sufficient grounds for the warrant to be issued in accordance with the laws of the Constitution and the United States. While the Court recognized that the affidavit did not disclose the fact that the Dumbra family held a federal permit allowing their store to sell wine for non-beverage purposes, the Court questioned whether the permit allowed the Dumbra family to avoid search and seizure of their businesses all together.

In the majority opinion, Justice Stone reasoned that the issuance of a federal permit for non-beverage purposes did not allow the permittee to possess intoxicating liquors for beverages purposes and thus did not afford protections to permittees who used the liquors in violation of the National Prohibition Act. Justice Stone concluded that, when a permittee intends to use its non-beverage permit for beverage purposes—thus violating the permit’s use—and if a warrant is lawfully issued, search and seizure is not unauthorized or unconstitutional. To this extent, the possession of a federal permit for non-beverage purposes was irrelevant.

In the majority opinion, Justice Stone reasoned that the issuance of a federal permit for non-beverage purposes did not allow the permittee to possess intoxicating liquors for beverages purposes and thus did not afford protections to permittees who used the liquors in violation of the National Prohibition Act. Justice Stone concluded that, when a permittee intends to use its non-beverage permit for beverage purposes—thus violating the permit’s use—and if a warrant is lawfully issued, search and seizure is not unauthorized or unconstitutional. To this extent, the possession of a federal permit for non-beverage purposes was irrelevant.

Justice Stone recognized that the federal agent should have revealed the existence of the federal permit when requesting the issuance of the warrant; however, the underlying illegal acts on behalf of the Dumbra family nullified the existence of the permit. Finally, the sale of the liquor to the federal agent was sufficient to show probable cause when issuing the warrant. The Court affirmed the order of the District Court, agreeing that the motion to quash the search warrant was properly denied by the lower court.

Images property of An Overview of The Prohibition Era: 1919-1933 and The Rose Melnick Medicinal Medicine, respectively.