There’s been some chatter recently about Uproot Wines and its newly introduced color-coded labels that represent the wine’s flavor palette. See, e.g., Millennials Targeted with Color-Coded Labels. The colored boxes on the true front label of the wine feature what Uproot Wines declares is a flavor palette, or a profile of what the wine in the bottle tastes like. The size of the boxes indicates how dominant a certain note is. For example, its 2011 Cabernet Sauvignon features a label with colored boxes in shades of raspberry, mustard yellow, burgundy, grape, and brown. The Cab’s flavor profile is said to correspond with these colors and consist of notes of raspberry, Cuban cigar, cherry, blackberry, and dark chocolate (with raspberry and blackberry appearing as the largest colored boxes and, hence, the most predominant notes). While the labels are unique, I’ll leave it to the marketers of the world to talk about the branding and design elements. Instead, I want to look at the labels from a legal perspective under 27 CFR Part 4, the relevant section of the Code of Federal Regulations on wine labeling and advertising. See generally 27 CFR Part 4 (outlining provisions of wine labeling and advertising regulations).

There’s been some chatter recently about Uproot Wines and its newly introduced color-coded labels that represent the wine’s flavor palette. See, e.g., Millennials Targeted with Color-Coded Labels. The colored boxes on the true front label of the wine feature what Uproot Wines declares is a flavor palette, or a profile of what the wine in the bottle tastes like. The size of the boxes indicates how dominant a certain note is. For example, its 2011 Cabernet Sauvignon features a label with colored boxes in shades of raspberry, mustard yellow, burgundy, grape, and brown. The Cab’s flavor profile is said to correspond with these colors and consist of notes of raspberry, Cuban cigar, cherry, blackberry, and dark chocolate (with raspberry and blackberry appearing as the largest colored boxes and, hence, the most predominant notes). While the labels are unique, I’ll leave it to the marketers of the world to talk about the branding and design elements. Instead, I want to look at the labels from a legal perspective under 27 CFR Part 4, the relevant section of the Code of Federal Regulations on wine labeling and advertising. See generally 27 CFR Part 4 (outlining provisions of wine labeling and advertising regulations).

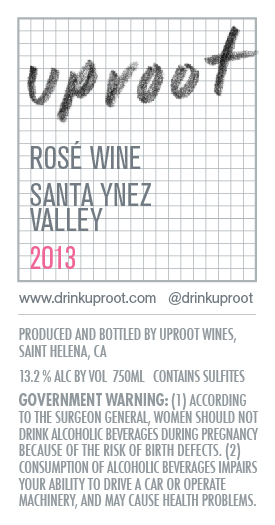

Generally speaking, like other wine labels within the labeling jurisdiction of the TTB, Uproot’s labels were pre-approved by the federal government. Such is evidenced by its Rosé Wine label approval here and its Grenache Blanc label approval here. Additionally, the true back labels of the wines produced by Uproot contain mandatory statements, such as the Alcohol by Volume statement, Net Contents Statement, and the Health Warning Statement. The true back label is a good example of the bare bones of a wine label, i.e., the back label contains only mandatory information that is required by federal law (with the exception of the website and social media addresses, which are considered to be voluntary information). I quite like the label design of these wines, and it left me wondering the following: are we heading toward a trend of textless wine labels? Or will demand for truth in labeling reign?

From a regulatory perspective, surely a textless label would make labeling specialists’ jobs easier and cut down the average processing time of a label (if not eliminate the processing time altogether). However, given that there are some requirements that must appear on a label, it is unlikely such requirements would disappear, especially after one considers the history and posture of these mandatory statements. If we were to ever come to a point where mandatory information was not required to be placed directly on a label, but could instead be viewed through a scannable Quick Response code (“QR code”), it is likely there would still be a level of government regulation with the type of information that could be presented (as well as the type that must be presented) by the scannable code. I can almost imagine a similar online submission process to COLAs Online, entailing the enduser to submit the information that appears through the scannable barcode to the government for prior approval.

From a marketing perspective, however, there are some features that producers may always want to keep on a wine’s label, such as a vintage year or an appellation of origin, so it is possible this aforesaid textless label may never appear discounting any regulatory reasonings. For some wines, the appellation may be the strongest branding for a wine produced and whose grapes are grown in a notable region whereas, for other wines, the brand name will always take precedence. These may be textual elements that, for marketing and other brand awareness purposes, may never leave a wine’s label. For Uproot, I think there is something to be said about placing a purely pictorial or graphic reference on the true front of its wine bottle as the focal point of the consumer, especially without referencing its brand name or producer (at least, not on the true front label). Its labels altogether are far off from a “textless” wine label, however its approach to minimalism is entirely respectable.

The age old story is, however, the law is persistently slow to catch up to innovation. Albeit, it is enjoyable to think about the possibilities that wine labels could take on. It should be noted, however, that it is TTB’s position that relevant sections of 27 CFR and the advertising provisions of the Federal Alcohol Administration Act (“FAA”) do apply to advertisements in social media, inclusive of QR codes and other 2D mobile barcodes that link to content that is a “written or verbal statement, illustration, or depiction that is in, or calculated to induce sales in interstate or foreign commerce.” See Use of Social Media in the Advertising of Alcohol Beverages.

Photographs property of Uproot Wines.

For more information on wine or alcohol law, labeling, or TTB matters, please contact Lindsey Zahn.

DISCLAIMER: This blog post is for general information purposes only, is not intended to constitute legal advice, and no attorney-client relationship results. Please consult your own attorney for legal advice.

From a design standpoint, I think these labels look great. But from a quality perspective, knowing the flavor profile won’t necessarily tell a consumer whether the wine is actually any good. Personally, my favorite wine labels are those of Ridge — nothing but dense blocks of text, telling me how long the growing season was, the quality of the harvest, the various percentages of the constituent varietals, the fermentation process, etc. But I am a nerd, lol.

Albert –

Thanks for the kind words, we have been trying to figure out how to balance the quality of wine with the beauty of the labels. Greg our winemaker has made wine at some of the top wineries in the valley. We are using really stringent farming techniques, top oak, all in small batch production to ensure awesome vino.

Jay