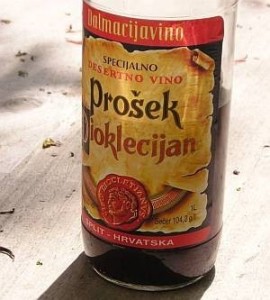

An article covering perhaps my favorite topic (intellectual property) in wine law emerged this last week. Unfortunately, or fortunately for On Reserve, the topic did not receive much attention amid major wine publications, but its content does not fail to intrigue at all (at least, not in my opinion). With Croatia’s accession to the European Union scheduled to occur this July, requirements such as the EU’s strict appellation rules must be followed by the joining country. Unfortunately—from the perspective of many Croatian winemakers—the beloved wine called Prošek will ceased to be bottled as such starting July 1, 2013. (See EU Prošek Ban Angers Croatian Winemakers – “Vino Dalmato” Replacement Term?) In March, “the [Croatian] agriculture ministry suddenly announced the traditional sweet dessert wine known as Prošek could no longer be sold under its name.” (Croatian Winemakers Upset by EU Label Rules.) Accordingly, in its negotiations, the EU claimed that the Croatian wine named Prošek is too similar to the name of to the effervescent Prosecco produced in Italy’s Veneto and Friuli Venezia Giulia wine regions. Prosecco currently enjoys legal protection under EU rules that govern other wines like Champagne and Port. The battle against Prošek draws a strong correlation to those endless crusades dueled by many Champagne producers: the demand for truth in labeling and place of origin.

While the names of the wines Prošek and Prosecco may linguistically be similar, the onset between these two wines is quite different from those fought by Champagne. Most, if not all, of the Champagne region’s battles seek to discontinue the use of the term “Champagne” on wine products that do not originate from the region. Most significantly, these wines are usually sparkling wines produced outside of Champagne, France and use the term “Champagne” to describe the style of the wine (or, in some cases, to feed off of the name Champagne and the region’s well-established wine products). Similar notions are seen for dessert wines like Port and Sherry. However, what is quite different in Prošek v. Prosecco is the fact that Prošek is actually a sweet dessert wine produced for centuries in Dalmatia and is not an effervescent wine, like Prosecco. (See EU madness hits Croatia: No More Prošek From July 1.) The two wines are also produced by exceptionally different methods, Prošek through the passito method and composed typically of grapes native to Croatia and Prosecco through the Charmat method (which requires a second fermentation).

Croatia filed an application to protect the term Prošek, but the European Commission requested that the Ministry withdraw said request. Not much is known about the EC’s request or why Croatia’s Ministry of Agriculture failed to explain the EC’s request to Croatian winemakers timely. “Unless Croatia manages to prove the difference and get the ban lifted, the local producers will have to change its name . . . .” (Croatian Winemakers Upset by EU Label Rules.) Unfortunately for Croatia, “[o]nly a few weeks later, Slovenia said Croatia had no right to produce and market teran, a red wine made in the northern tip of the Adriatic, shared by Italy, Slovenia and Croatia.” (Id.)

Photograph property of No More Famous Croatian Prošek From 1 July.