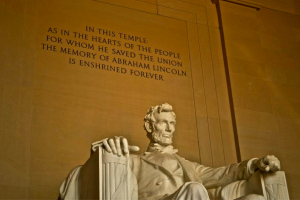

We moved to D.C. in August, and with a transfer from a city like New York to a city like Washington, D.C., comes (perhaps) a greater level of awareness—at least, of governmental regulation. Every day, I am surrounded by the architecture of great minds (and great buildings), and every day I think more about the intersections and the mutual exclusiveness of alcohol beverage and food regulation. After becoming associated with a food and beverage law firm, my daily deductions swerved from wine to an immediate indulgence of food (and beverage).

Since starting my work here, I deal a lot with food issues, and I am grateful for the opportunity to do so. Becoming conversant with both food and alcohol regulations means noticing the differences of each—how each are defined and how each are regulated. The Food and Drug Administration (“FDA”) regulates food in the United States and the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (“TTB”) regulates alcohol beverages in the United States. Plainly put, the aforesaid seems uncomplicated and clear, but in practice, the lines separating alcohol beverages and food can be controversial.

Since starting my work here, I deal a lot with food issues, and I am grateful for the opportunity to do so. Becoming conversant with both food and alcohol regulations means noticing the differences of each—how each are defined and how each are regulated. The Food and Drug Administration (“FDA”) regulates food in the United States and the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (“TTB”) regulates alcohol beverages in the United States. Plainly put, the aforesaid seems uncomplicated and clear, but in practice, the lines separating alcohol beverages and food can be controversial.

One of the areas of wine and food law of utmost interest to me is the clear difference in labeling. Very generally speaking, TTB has jurisdiction over the labeling of wine containing 7.0% alcohol by volume or greater (e.g., table wine, dessert wine, etc.) while the FDA has labeling jurisdiction over wines containing less than 7.0% alcohol by volume. (Again, this is a generalization; low-volume alcohols are still required to maintain certain requirements stipulated by TTB, and certain wines, depending on the context, may be required to comply with FDA labeling regulations.)

Perhaps one of the clearest differences between FDA labeling and TTB labeling is the requirement that food labels (as regulated by FDA) contain nutrition fact panels and ingredient statements. Two pieces that remain absent from the labels of most wines are the nutrition facts panel and the ingredients statement. And the question posed by this is simple: why not? With the increased trend of consumer awareness and the desire to know how many calories are present in items consumed, the exact ingredient contents, and various nutrition information, why are nutrition fact panels and ingredient statements not found on the labels of most alcohol? (See Alcohol Industry Grapples with Nutrition Labeling.)

While history suggests that TTB (and its predecessor agency, ATF) contemplated requiring nutrition fact panels on alcohol beverages, no measures in furtherance of securing a nutrition fact panel or ingredients list have occurred. (See TTB Issues Ruling on Use of Caloric and Carbohydrate Claims in Advertising and Labeling in Alcoholic Beverages; see also TTB Proposed “Serving Facts” Label and Alcohol Content Statement on All Beverage Alcohol Labels.) In part, this may be due to lack of consumer interest or concern. More so, the impact on the industry may be extremely costly; for wines, wineries could face the requirement of having every vintage and variety to be analyzed for proper nutrition facts and content. Of course, doing so would increase the cost of producing a wine. Perhaps the alternative is to consider an allowance for a more generalized analysis, as opposed to analyzing every vintage and every variety.

But with products like Skinnygirl, purporting “lower calories” and seemingly attractive to calorie-conscious consumers, on the market, one wonders if the lack of a nutrition facts panel and ingredients statement is proper. On a food label under the jurisdiction of FDA, there are regulations from the agency indicating how and in what contexts certain claims (like “low calories”) can be used. (This is not to indicate that TTB does not have similar–products like Skinnygirl do proclaim calorie count and other nutrient counts like fat, but the format is not of a nutrition facts panel nor do such declarations include all nutrients found on a typical nutrition facts panel.) But forget products like Skinnygirl for a moment–aren’t consumers entitled to know what is in any beverage product, even if no “low calorie” claims are made? Such alcohol beverage products are even less likely to disclose items like calorie count and fat. Is this right? Are we living in a time where there is an increased desire for consumer knowledge on food and beverage products, not excluding alcohol beverage labels?

While the full nutrition facts panel that appears on foods many not be ideal on alcohol beverage labels (for sizing, formatting, cost, and aesthetic reasons), one might still ponder why the TTB is yet to require at least a basic nutrition label and ingredients statement on all products under its jurisdiction. But maybe a more appropriate question is as follows: should the nutrition facts and ingredients be a consideration when a consumer purchases an alcohol beverage (and has such ever really been of concern to most alcohol consumers)?

Photograph property of Lindsey A. Zahn

For more information on wine or alcohol law, labeling, advertising, or FDA or TTB matters, please contact Lindsey Zahn.

DISCLAIMER: This blog post is for general information purposes only, is not intended to constitute legal advice, and no attorney-client relationship results. Please consult your own attorney for legal advice.

Lindsey,

Thanks for this piece. As someone with food allergies, I would love to see beer (moreso than wine) disclose ingredients. With the continued innovation in craft beers using all kids of different fruits, vegetables, and other products (oysters, etc…), I get a little nervous about beers that I cannot readily identify the ingredients. A great example Six Point’s 3beans. It has chocolate, coffee, and a legume (which is out for me). I found that out from the website, but it being on the label would be even easier so I don’t consume something that will make me sick.

Just my two cents of course. For now, I will just use Google and look stuff up on my own!

dctravel (Jake)

The real issue for wineries (besides the asthetics) is the nature of the winemaking process.

First, wine production involves the use of processing aids, which are just about, but maybe not quite 100% removed by further processing. Typically these processing aids are only used on an as needed basis on individual lots. Should ingredients be listed if there is no detectible trace left? What burden is there to prove this?

Second, quality wine production is not as formula driven as most foods. Each wine lot is given individual attention up until the final blend is made. Final wine blends are typically made very close to the time of bottling, well after labels have already been printed. If a last minute blend change makes the label innacurate, then what?

I’d like to see the amount of sulfites, or at the very least ADDED sulfites, revealed in the labeling of all wine. I am sensitive to sulfites and have to do extensive research to learn which brands/winemakers do not add sulfites to their wine, relying on only the natural sulfites in the grapes.