The Volstead Act: the legislative measure whose primary intent was to frame the execution of the Eighteenth Amendment, a curt and inexorable constitutional revision whose overtones still reside in contemporary American society even upon its repeal almost one hundred years ago. The legal supremacy of the Eighteenth Amendment, however, often overshadows the real authority hidden within the Volstead Act of 1919. In actuality, the Eighteenth Amendment displays limited vigor and certainly lacks appropriate legislative clauses and actions that permit its objective to flourish. Its text, which remains in our present-day Constitution, reads as follows:

The manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors within, the importation thereof into, or the exportation thereof from the United States and all territory subject to the jurisdiction thereof for beverage purposes is hereby prohibited.

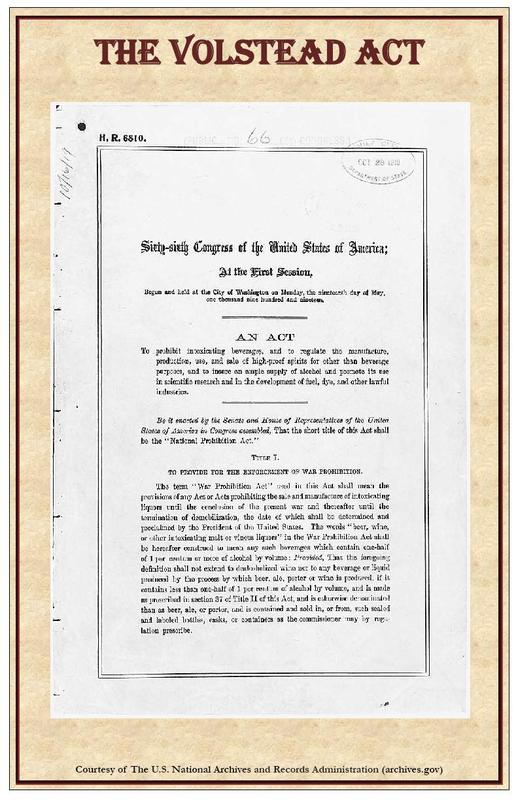

The vagueness of the Eighteenth Amendment leaves the reader with a multiplicity of questions, some of which include: What are “intoxicating liquors”? What is meant by “for beverage purposes”? And what, exactly, entails the “manufacture” or the “sale” or the “transportation” of such substances for such purposes? The ambiguity of the Eighteenth Amendment would have, on its face, left the amendment void for vagueness. However, the United States Congress passed the National Prohibition Act, or the Volstead Act, on October 28, 1919 despite the veto of the then-President Wilson. The answers to the aforesaid questions lie within the text of the extended Volstead Act.

The Eighteenth Amendment became effective on January 16, 1920, a year after the Nebraska State Legislature ratified the Amendment and triggered the required two-thirds majority support for the Amendment to become law in the States. The Volstead Act was passed on October 28, 1919, shortly after Nebraska’s ratification, its name attributive to Andrew Volstead, a Republican congressman from Minnesota who reportedly drafted the bill. (It is also claimed that Wayne B. Wheeler, legal counsel for the Anti-Saloon League of America, was the creator and force behind the bill.)

The Act itself is divided into two Titles: (1) To Provide for the Enforcement of War Prohibition; and (2) Prohibition of Intoxicating Beverages. For the purposes of alcohol prohibition (or Prohibition), the greater focus remains on the second title of the act, which is in turn divided into subsequent sections. However, the first title does define exactly what is meant by “intoxicating liquors.”

What are the key provisions of the Act?

The Volstead Act refines the intentions of the Eighteenth Amendment, although it is not without its own imperfections. Title II, Section 3 of the Act maintains that, “[n]o person shall . . . manufacture, sell, barter, transport import, export, deliver, furnish or possess any intoxicating liquor except as authorized in this Act, and all the provisions of this Act shall be liberally construed to the end that the use of intoxicating liquor as a beverage may be prevented.” The Act did not prohibit the consumption of intoxicating beverages, at least not directly and not entirely. In fact, the Volstead Act did explicitly exempt wine for sacramental purposes and liquor or alcohol proscribed by a physician for medicine (see infra.).

Most importantly, however, the Volstead Act clarifies the Eighteenth Amendment’s indistinct phrase of “intoxicating liquors.” Title I of the Volstead Act states, “[t]he words ‘beer, wine, or other intoxicating malt or vinous liquors’ . . . shall be hereafter construed to mean any such beverages which contain one-half of 1 per centum or more of alcohol by volume . . .” Before the Eighteenth Amendment was enacted, many producers of fermented beverages like wine and beer, thought their products would be precluded from the Amendment and that the Amendment would only restrict alcoholic beverages with higher alcohol per volume, such as distilled spirits (hard liquor). During the push for the ratification of the Eighteenth Amendment, congressmen and the media particularly focused on the more “evil” and most alcoholic distilled spirits, thus allowing producers of wine and beer to believe they might not only evade the financial misfortunes of the Eighteenth Amendment but also flourish from the elimination of the distilled spirits market share. With the addition of the Volstead Act, however, these beliefs became misguided; Title I includes wine and beer under its definition of “intoxicating liquors,” as both wine and beer contain more than .5% alcohol by volume.

What are the exceptions of the Act?

Despite the restrictive measures of the Volstead Act, it allows for some deviations from its control. Section 3 of Title II reads, “[l]iquor for non beverage purposes and wine or sacramental purposes may be manufactured, purchased, sold, bartered transported, imported, exported, delivered, furnished and possessed, but only as herein provided . . .” Additionally, section 6 of Title II reads, “a person may, without a permit, purchase and use liquor for medicinal purposes when prescribed by a physician . . . and except that any person who in the opinion of the commissioner is conducting a bona fide hospital or sanitarium engaged in the treatment of persons suffering from alcoholism, may . . . purchase and use . . . liquor . . .” Additional exceptions include the use of alcohol for “non-beverage” purposes (i.e. industrial use), such as for paints, chemicals, in manufacturing other products, etc.

NOTE: The Eighteenth Amendment was repealed by the ratification of the Twenty-First Amendment in 1933. The National Prohibition Act, or the Volstead Act, is—to this day—unconstitutional.

(Image Credit: The 18th Amendment and Greenwich Village History, respectively.)

For more information on wine or alcohol law, Prohibition, direct shipping, or three-tier distribution, please contact Lindsey Zahn.

DISCLAIMER: This blog post is for general information purposes only, is not intended to constitute legal advice, and no attorney-client relationship results. Please consult your own attorney for legal advice.

The Volstead Act was a mishmash of special interest legislation. It allowed families to produce up to 200 gallons of “fruit juices” for home consumption which included both wine and (hard) apple cider. This exemption, coupled with reduced availability of other forms of alcoh0l, caused an increase in price of California grapes and a doubling of winegrape acreage in the years immediately after the enactment of the 18th Amendment

Nice work on the analysis of the Volstead Act.

I always got confused with the dichotomy of possession was illegal, but consumption was legal…

I hope you’ll join us on the Wine Harlots favorite holiday, Repeal Day (December 5th) and celebrate with a glass of intoxicating spirits.

Cheers to you!

Nannette Eaton

Lecture Notes:

The War Prohibition Act

Attempts to control consumption of alcohol in America have been with us for some time. The first laws were passed by the Colony of New York in 1697 closing saloons on Sundays. Many colonies, states, counties and towns followed suit over the decades. The village of Oberlin was created in 1836 on a 500-acre tract of virgin forest located 34 miles southwest of Cleveland, Ohio. A couple of years before, the Oberlin Collegiate Institute (today, it is known as Oberlin College) was started by abolitionist Congregational Christians. It was the first coed university in America, the first to admit blacks as the equal to whites, and it was a station for the Underground Railroad during the Civil War. Some claim the Civil War started in Oberlin. Oberlin has long been associated with progressive causes. However, the progressive new village and college both banned alcohol.

In May of 1893, the Reverend Howard Russell, an Oberlin alumnus, visited the campus. He was on a mission. An alcoholic brother had turned him against liquor, and since leaving Oberlin he had been associated with the Temperance Alliance. His sermons resulted in the closing of several saloons throughout the region. Upon his visit to Oberlin, he convinced the citizens to create the Ohio Anti-Saloon League. He was made superintendent. Temperance circles around the country soon followed suit, and in 1895 the Anti-Saloon League of America was created.

By 1913, the League lobbied and helped elect “dry” candidates to offices. It was then that several members of the League, including the Reverends Purley Baker, James Cannon, Jr. and Wayne Bidwell Wheeler, drafted a proposed 18th Amendment to the Constitution. It basically stated, “…sale, manufacture for sale, transportation for sale, importation for sale, and exportation for sale, of intoxicating liquors for beverage purposes in the United States and all territory subject to the jurisdiction thereof are forever prohibited.” The draft was given to two dry legislators: Democratic Senator Morris Sheppard of Texas and Democratic Congressman Richmond Pearson Hobson of Alabama. The Hobson-Sheppard resolution was submitted to the appropriate committees of both congressional chambers. The debates concerning alcohol sale and consumption went on in Congress, but no action was taken at that time. President Woodrow Wilson had voiced his opposition to the amendment. Wilson was pro-temperance but against the constitutional amendment. As he said: “There is no temperance in it!”

The dries picked up more seats in both congressional houses in the 1914 elections. Still, nothing took place on the Hobson-Sheppard resolution until 1917. On April 16, 1917, Woodrow Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany. A vital part of Wilson’s plan was a food control bill designed to direct vital food materials to aid in the war effort. The League members saw an opportunity. Because hard liquor production required grain, sugar and other items, they used strong patriotic arguments against liquor. They also found some dry military officers who would speak about keeping soldiers free from liquor and maintaining their sound minds.

They also went after the beer industry as being pro-German and treasonable. Most brewers had German names and they were easy targets. Post 9/11 French criticism over the invasion of Iraq resulted in a similar reaction by some members of the US congress. The cafeteria at the US House of Representatives changed its menu and offered “Freedom Fries” and “Freedom Toast”. Similarly, the League and their backers renamed sauerkraut as “Liberty Cabbage”. After much wrangling, a food bill passed on September 17, 1917. It banned hard liquor but did not touch beer or wine.

Meanwhile, Wayne Bidwell Wheeler went back to the original 18th Amendment draft, modified the language to satisfy the states rights people and gave it back to his friends in Congress. By December 18, 1917, the 18th Amendment to the Constitution had passed both houses of Congress. Ironically, the final version of the 18th Amendment (The War Prohibition Act) was passed ten days after the armistice ending WW I.

The amendment then went to the states for ratification. It became law on January 16, 1919, two months after hostilities stopped. The Leagues main argument for passage had been wartime urgency.

AMENDMENT XVIII Passed by Congress December 18, 1917. Ratified January 16, 1919.

Section 1. After one year from the ratification of this article the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors within, the importation thereof into, or the exportation thereof from the United States and all territory subject to the jurisdiction thereof for beverage purposes is hereby prohibited.

Section 2. The Congress and the several States shall have concurrent power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

Section 3. This article shall be inoperative unless it shall have been ratified as an amendment to the Constitution by the legislatures of the several States, as provided in the Constitution, within seven years from the date of the submission hereof to the States by the Congress.

The Anti-saloon League and temperance movement’s long quest was seemingly brought to a triumphant conclusion. But other little noticed elements were at play.

The Federal Income Tax amendment was passed in 1913, and its revenue raising ability was quickly realized. Revenues in 1917 were nearly three times those in 1916. Congress amended the income tax in October of 1917, and revenues increased substantially in 1918. This revenue legislation passed just two months prior to the initial proposal of the 18th Amendment. Prior to the income tax amendment, tariffs and alcohol taxes provided the bulk of federal government revenues. Between 1870 and 1920, customs and liquor taxes provided nearly 80% of all federal revenue.

With the 18th Amendment, lost federal alcohol tax revenues were more than recovered by income taxes. The income tax supplied two-thirds of federal revenue by 1918 and by 1920 income taxes dominated customs and liquor taxes by a ratio of 9 to 1. The massive increase in income taxes removed Congress’s need for alcohol tax revenues and created the opportunity for the passage of the 18th Amendment. Some feel that the income tax tipped the balance in politicians’ cost-benefit calculations in favor of voting dry by lowering the cost of voting for prohibition.

Now a method of enforcement had to be enacted. At the Anti-Saloon League, Wayne Wheeler drafted a National Prohibition Act. He gave it to Representative Joseph Volstead of Minnesota. Volstead introduced it to the House. Even though the Congressman had nothing to do with authorship, it was known as the Volstead Act. In actual fact, Volstead never had delivered a temperance speech nor signed a temperance pledge. It was said he took an occasional nip and was quoted as saying “I don’t know that there’s harm in one drink?” He opposed a few prohibitionist candidates in his six elections to the House. But, he was chairman of the House Judiciary Committee and Wheeler’s final draft fell into his lap.

Several sections of the Volstead Act were modified before the final act was passed by Congress. Among those trying to get the language in the Act changed was Paul Garrett. He lived in Brooklyn, NY, and owned vineyards in California. He managed to secure a hearing before Congress to speak on behalf of the grape growers. He, along with other growers, presented their case. At the hearing was the Reverend E.C. Dinwiddie, the legislative superintendent of the Anti-Saloon League. Since the League authored both the 18th Amendment and the Volstead Act, the Reverend was center stage at these congressional hearings.

Dinwiddie repeatedly assured the grape growers that the League was concerned about the welfare of grape growers and had no desire to cause the growers hardship or losses. He suggested the League would aid growers in marketing their harvests. He even suggested that de-alcoholized wines could be made and sold, thus giving the growers a steady market. It was pointed out that before de-alcoholization could occur, alcohol had to be produced via fermentation. So Dinwiddie was entertaining the idea of wine being produced for ultimate de-alcoholization to less than ½%.

Garrett later met with Dinwiddie and Wheeler at the League office to discuss the Act. The League wrote a new clause into the Act allowing wine to be produced for medicinal, sacramental and de-alcoholization purposes. Also discussed was the right of individuals to make wine in their home for personal use. Nobody believed this small gesture would in any way benefit the grape grower, so it never was considered to be significant by anybody. It was felt by all that this would involve a very small amount of grapes. Also, nobody wanted to offend housewives by denying them the right to make a few jars of fruit wine from their own or wild grapes or berries.

The result of the wishes to look out for grape growers and home winemakers (especially the housewives) was the addition of Section 29, Title II to the Volstead Act: “…The penalties provided in this chapter against the manufacture of liquor without a permit shall not apply to a person manufacturing nonintoxicating cider and wine exclusively for use in his home, but such cider and wine shall not be sold or delivered except to persons having a permit to manufacture vinegar.”

The original version had wine in it. Some very dry members of Congress objected. Wine was replaced by fruit juices. Even though nonintoxicating fruit juice seemed to have no resemblance to wine, the League assured Garrett and the growers that they were prepared to disregard the Volstead’s definition of intoxicating and to accept wine made at home as “nonintoxicating in fact.”

The Volstead Act, officially titled the “National Prohibition Act,” was passed on October 18, 1919 and went into effect February 1, 1920. It effectively outlawed the production and sale of alcoholic beverages. It started with:

TITLE I. TO PROVIDE FOR THE ENFORCEMENT OF WAR PROHIBITION.

The term “War Prohibition Act” used in this Act shall mean the provisions of any Act or Acts prohibiting the sale and manufacture of intoxicating liquors until the conclusion of the present war and thereafter until the termination of demobilization, the date of which shall be determined and proclaimed by the President of the United States. The words “beer, wine, or other intoxicating malt or vinous liquors” in the War Prohibition Act shall be hereafter construed to mean any such beverages which contain one-half of 1 per centum or more of alcoholic beverages by volume.

After the bill passed Congress, Garrett met with the League principals again and was reassured the word “nonintoxicating” would not apply to home winemakers. This was not clear to Garrett. It was still up to the Treasury Department to get involved, since Congress had fixed no limit on the amount of “nonintoxicating” fruit juice or cider that could be made tax free by individuals. The Bureau’s interpretation stated that “…any person may without permit…manufacture non-intoxicating cider and fruit juices…and…must be used exclusively at home, and when so used the phrase ‘non-intoxicating’ means non-intoxicating in fact and not necessarily less than one-half of one per cent of alcohol as provided in Section 1 of Title II of said act.”

So, how much “non-intoxicating cider and fruit juices” could an individual make? That has always been decided by the Internal Revenue Service. Presently, CFR Title 27, Part 1, Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms states in § 24.75, Wine for personal or family use: (a) General. Any adult may, without payment of tax, produce wine for personal or family use and not for sale. (b) Quantity. The aggregate amount of wine that may be produced exempt from tax with respect to any household may not exceed: (1) 200 gallons per calendar year for a household in which two or more adults reside, or (2) 100 gallons per calendar year if there is only one adult residing in this household.

During Prohibition there was REGULATIONS 60 RELATIVE TO INTOXICATING LIQUOR, Revised March 1924. Article VI. Manufacture of cider, vinegar and nonintoxicating fruit juices. Section 615 stated in print: “Under the internal revenue laws persons producing fruit juice, other than cider, containing one-half of 1 percent or more of alcohol by volume, are required to establish bonded premises and pay wine tax on the quantity removed from such premises, unless they come within the 200-gallon tax-free exemption provided in section 616 of the internal revenue act of 1918.”

Apparently the family wine tax exemption dates from 1916. So, since 1916 the Internal Revenue Service has allowed that a head of household, and spouse, could make 200-gallons of fruit juice or wine a year.

The conflicting definitions of “intoxicating” of the Volstead Act were left unchallenged until Maryland Congressman John Philip Hill tried to get the Bureau of Prohibition to clarify Section 29. In 1923 Hill made wine at his Baltimore home. He invited the Bureau to his house and gave them a sample. After analysis, the Bureau secured a temporary injunction against Hill and padlocked his wine cellar. In 1924 Hill made cider. Again, he invited everyone to his house to taste his homemade cider. People from the Anti-Saloon League and Bureau of Prohibition were also invited. None came. However, this time, Hill was indicted, not arrested, for violation of the Volstead Act for illegally manufacturing wine and cider.

The District Court in Baltimore was given the case. The judge held that Hill was entitled to show evidence that his cider was not intoxicating “in fact”; i.e., that the definition of intoxicating in the Volstead Act did not apply to home production of alcoholic beverages. The jury ruled that Hill’s cider did not, in fact, intoxicate. Until Hill forced the ruling, home winemaking was taking place with uncertainty regarding the Volstead Act. After the Hill case, producing cider and wine at home was considered to be legal by all, as long as the result was “nonintoxicating in fact”. Since no one knew precisely what “nonintoxicating in fact” was, the Bureau of Prohibition left home winemakers alone.

A parallel case before the Circuit Court of Appeals on October 20, 1925 was Isner vs. United States in which a previous ruling by the US District Court was overturned. Creed Isner had been convicted of manufacturing intoxicating liquor. The District Court ruled that Isner be indicted and convicted for unlawfully possessing “intoxicating liquor, to wit, 70 gallons of grape wine.” The main facts showed that Isner had a quantity of wild cherries and elderberries, and had made an effort to get a permit from the state authorities to make wine out of them. The berries were grown on his own farm. He put them into a barrel and strained out the berries, having added about two gallons of water to one gallon of juice. Having failed to secure a permit, he placed the barrel containing the juice and water in an outside cellar, where state police officers found it. The contents of the barrels were not destroyed by the officers, but pint samples were taken from the barrels. There was much disputed testimony as to whether or not this concoction was fit for beverage purposes. A number of witnesses said it “was so bitter that it could not be drunk,” and others said that it tasted like wine. The pint samples were analyzed, but the record does not show the alcoholic content. Isner offered to show that the liquid was not intoxicating, but objection to this evidence was sustained by the District Court judge.

The final clause of Section 29 of the Volstead Act reads: “The penalties provided in this chapter against the manufacture of liquor without a permit shall not apply to a person manufacturing nonintoxicating cider and fruit juices exclusively for use in his home, but such cider and fruit juices shall not be sold or delivered except to persons having a permit to manufacture vinegar.” According to the Court of Appeals, this provision meant that Creed Isner could not be convicted of violating the Volstead Act unless the government showed that his watered-down cherry and elderberry juice mixture was in fact intoxicating. The government chose not to do so, stipulating that Isner’s wine was not intoxicating. It argued that “this concoction or beverage, although not intoxicating, comes under the general prohibition in the act defining liquor,” i.e., “such beverages which contain one-half of 1 per centum or more of alcohol by volume.” In his brief, the United States attorney wrote, “In order that the question may be settled squarely on the construction of the last clause of Section 29 (of the Volstead Act), the government concedes here and now that the said wine was not, as a matter of fact, intoxicating.”

The Appeals Court concluded that the last clause of Section 29 made an exception to this general definition, such that the “grandmother and housewife” would not be “penalized and made criminals if they made blackberry cordials or blackberry wines for use in their own home.” The exception was pragmatic but illogical since it rested on the premise that homemade “cordials or wines” could be alcoholic enough to warrant the trouble without being “intoxicating.”

So what happened to the grape growers during Prohibition? Did the housewives make very many jars of wine? From 1925 to 1929, Americans drank more than 678 million gallons of homemade wine. That was three times as much as all the domestic and imported wine they drank during the five years before Prohibition.

Bearing vineyard acreage in California in 1920 was about 300,000 acres; by 1927, it hit 577,000 acres. Grapes harvested went from 1.25 million tons in 1920 to 2.5 million tons in 1927. That’s a lot of jars of wine.

A major problem also arose. The 18th Amendment passed congress in 1917 and was ratified by the states in 1919 and the Volstead Act passed shortly thereafter. Meanwhile, WW I ended in 1918 and thousands of veterans were returning home. Most of these vets had been stationed in France. They had become accustomed to having a glass of wine with their meals. They won a war, returned to their homeland and were told they couldn’t buy a bottle of wine. They were a bit bitter. The vets were not on the sides of the “dries”.

Besides home winemaking, there were other clever ways of manufacturing and even selling “non-intoxicating” cider and fruit juices. In Manhattan, a salesgirl gave a demonstration about a new beverage. On a counter before her were displayed solid bricks of grape concentrate. She took an empty gallon jug and told her audience that all they had to do was put a pre-measured brick in a gallon jug, add water almost to the top, swirl it around, and, violá, you have grape juice.

She cautioned that the juice “has to be used immediately”.

She added that:

“The buyer should not put the water in the jug and mix the concentrate and then put the jug away in the cupboard for 21 days. It might, then, turn into wine.

Do not put the cork and patented red rubber siphon hose in the top of the bottle. (These she sold as accessories along with the gallon jugs.) That is only necessary if fermentation is taking place.

Do not put the end of the siphon hose in a glass of water. That is only needed to ensure that fermenting wine is sound and drinkable.

Do not shake the bottle once a day. That would excite yeast in a fermenting wine.”

By days end, she usually sold hundreds of blocks of Port, Sherry, Burgundy and Rhine concentrate, jugs and accessories. If her warnings were ignored, the bricks would produce 13% alcohol wine.

The problems faced by the United States during Prohibition are well known. With the Crash of 1929 and start of the economic depression, the drys were losing allies. Both Hoover and Roosevelt pledged repeal of the 18th Amendment. A month following Roosevelt’s landslide victory, Republican Senator John Blaine of Wisconsin drafted a resolution calling for the repeal of the 18th Amendment. Congress passed the resolution and it was sent to the states. With ratification of the 21st Amendment on December 5, 1933, the 18th Amendment was repealed. The conclusive proof of Prohibition’s failure is, of course, the fact that the 18th Amendment became the only constitutional amendment to be repealed.

During the Depression, the populations of the big cities of America increased, partly because people came to the cities looking for work. As a result, the cities experienced increased expenditures due to public support needs. There were also left over infrastructure expenses related to WWI. At the same time, the cities had great difficulties in finding needed funds. One of the major factors which lead to plummeting local revenue was the loss of alcohol taxes.

Repeal of the 18th Amendment allowed local, state and federal government to reinstate alcohol taxes and increase revenues. State and local governments also gained additional revenue via licensing fees and other alcohol related charges, and federal alcohol taxes freed up additional money that could be provided to state and city governments in the form of grants, public works, and other assistance. These revenue flows permitted property tax cuts and other tax cuts. Repeal also reduced spending on the enforcement of Prohibition, reduced political corruption, and greatly reduced crime in America.

It is felt that popular sentiment for repeal was less important in propelling the 21st Amendment than was Congress’s desire for increased revenues combined with interest group pressures for lower income tax rates. The tax revolt primarily focused on income taxes. The renewed infusion of alcohol taxes helped to keep the income taxes lower. In fact, repeal of the 18th Amendment worked in conjunction with the bulk of taxpayers being given an income tax cut beginning in 1934.

~

Acknowledgements must be given to Laurel Indalecio, great-great grand niece of Creed Isner, Jacob Sullum, Senior Editor, Reason, Marjorie D. Ruhl, TTB Regulations and Rulings Division, Todd J. Zywicki, Professor of Law, George Mason University School of Law, William Bushong, Historian and Webmaster, White House Historical Association, Frank Aucella, Executive Director, Woodrow Wilson House and Carl Sferrazza Anthony, Consulting Historian, National First Ladies Library for their ideas, directions and stories. Finally, I must thank Walt Kelly for giving the best overview of this part of American history. . He is known for a poster he created in 1970 on which Pogo states: “We have met the enemy and he is us.”

References:

1. John Kobler, Ardent Spirits. The Rise and Fall of Prohibition. 1973.

2. Gaye Lebaron, “Turns out that homemade wine in Prohibition wasn’t legal”, The Press Democrat, October 22, 2006.

3. Regulations 60 Relative to Intoxicating Liquor. Revised March 1924. Washington. Article VI. Manufacture of Cider, vinegar, and nonintoxicating fruit juices.

4. “Calls For Repeal of Volstead Act” New York Times.

5. “The Volstead Act, October 28, 1919.” Historical Documents in United State History. http://www.historicaldocuments.com/VolsteadAct.htm

6. “Not Guilty” Time, Monday, November 24, 1924. http://www.time.com/time/printout/0,8816,719465,00.htm

7. Paul Garrett, ‘The Right to Make “Fruit Juices”’, California Grape Growers, 4 (July 1923) 2-3.

8. Thomas Pinney, A History of Wine in America, 2005

9. US Dept. of Agriculture, Bureau of Agricultural Economics, Crop Reporting Board, Fruits and Nuts Bearing Acreage, 1919-1946

10. David T. Beito, Taxpayers in Revolt: Tax Resistance during the Great

Depression (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1989)

11. Donald Boudreaux and A.C. Pritchard, “The Price of Prohibition,” Arizona Law Review,

36( 1994): 1-10.

12. Jack S. Blocker, Jr, “Did Prohibition Really Work? Alcohol Prohibition as a Public Health Innovation”, Am J Public Health. 2006 February; 96(2): 233–243.

13. Bruce Allen Hardy, “American Privatism and the Urban Fiscal Crisis of the Interwar Years: A Financial Study of the Cities of New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, Detroit, and Boston, 1915-1945,” Dissertation Wayne State University, 1977.

14. Joseph T. Salerno, “War and the Money Machine: Concealing the Costs of War Beneath the Veil of Inflation,” The Costs of War: America’s Pyrrhic Victories, 2nd edition edited by John V. Denson (New Jersey: Transaction Publishers, 1999)

Volstead Act in Consulting Folder

George Vierra 25 February 2008

Viticulture & Winery Technology

Napa, CA USA

gjvnapa@sbcglobal.net