Happy National Repeal Day! In honor of the repeal of the National Prohibition Act on December 5, 1933, we thought it appropriate to re-post an article originally written two years ago on the Volstead Act. See Revisiting the Volstead Act: The Power Behind the Eighteenth Amendment for Prohibition; see also Revisiting the Roads to Prohibition: The Maine Laws.

The Volstead Act: the legislative measure whose primary intent was to frame the execution of the Eighteenth Amendment, a curt and inexorable constitutional revision whose overtones still reside in contemporary American society even upon its repeal almost one hundred years ago. The legal supremacy of the Eighteenth Amendment, however, often overshadows the real authority hidden within the Volstead Act of 1919. In actuality, the Eighteenth Amendment displays limited vigor and certainly lacks appropriate legislative clauses and actions that permit its objective to flourish. Its text, which remains in our present-day Constitution, reads as follows:

The manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors within, the importation thereof into, or the exportation thereof from the United States and all territory subject to the jurisdiction thereof for beverage purposes is hereby prohibited.

The vagueness of the Eighteenth Amendment leaves the reader with a multiplicity of questions, some of which include: What are “intoxicating liquors”? What is meant by “for beverage purposes”? And what, exactly, entails the “manufacture” or the “sale” or the “transportation” of such substances for such purposes? The ambiguity of the Eighteenth Amendment would have, on its face, left the amendment void for vagueness. However, the United States Congress passed the National Prohibition Act, or the Volstead Act, on October 28, 1919 despite the veto of the then-President Wilson. The answers to the aforesaid questions lie within the text of the extended Volstead Act.

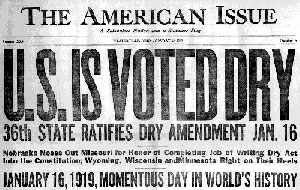

The Eighteenth Amendment became effective on January 16, 1920, a year after the Nebraska State Legislature ratified the Amendment and triggered the required two-thirds majority support for the Amendment to become law in the States. The Volstead Act was passed on October 28, 1919, shortly after Nebraska’s ratification, its name attributive to Andrew Volstead, a Republican congressman from Minnesota who reportedly drafted the bill. (It is also claimed that Wayne B. Wheeler, legal counsel for the Anti-Saloon League of America, was the creator and force behind the bill.)

The Act itself is divided into two Titles: (1) To Provide for the Enforcement of War Prohibition; and (2) Prohibition of Intoxicating Beverages. For the purposes of alcohol prohibition (or Prohibition), the greater focus remains on the second title of the act, which is in turn divided into subsequent sections. However, the first title does define exactly what is meant by “intoxicating liquors.”

What are the key provisions of the Act?

The Volstead Act refines the intentions of the Eighteenth Amendment, although it is not without its own imperfections. Title II, Section 3 of the Act maintains that, “[n]o person shall . . . manufacture, sell, barter, transport import, export, deliver, furnish or possess any intoxicating liquor except as authorized in this Act, and all the provisions of this Act shall be liberally construed to the end that the use of intoxicating liquor as a beverage may be prevented.” The Act did not prohibit the consumption of intoxicating beverages, at least not directly and not entirely. In fact, the Volstead Act did explicitly exempt wine for sacramental purposes and liquor or alcohol proscribed by a physician for medicine (see infra.).

Most importantly, however, the Volstead Act clarifies the Eighteenth Amendment’s indistinct phrase of “intoxicating liquors.” Title I of the Volstead Act states, “[t]he words ‘beer, wine, or other intoxicating malt or vinous liquors’ . . . shall be hereafter construed to mean any such beverages which contain one-half of 1 per centum or more of alcohol by volume . . .” Before the Eighteenth Amendment was enacted, many producers of fermented beverages like wine and beer, thought their products would be precluded from the Amendment and that the Amendment would only restrict alcoholic beverages with higher alcohol per volume, such as distilled spirits (hard liquor). During the push for the ratification of the Eighteenth Amendment, congressmen and the media particularly focused on the more “evil” and most alcoholic distilled spirits, thus allowing producers of wine and beer to believe they might not only evade the financial misfortunes of the Eighteenth Amendment but also flourish from the elimination of the distilled spirits market share. With the addition of the Volstead Act, however, these beliefs became misguided; Title I includes wine and beer under its definition of “intoxicating liquors,” as both wine and beer contain more than .5% alcohol by volume.

Most importantly, however, the Volstead Act clarifies the Eighteenth Amendment’s indistinct phrase of “intoxicating liquors.” Title I of the Volstead Act states, “[t]he words ‘beer, wine, or other intoxicating malt or vinous liquors’ . . . shall be hereafter construed to mean any such beverages which contain one-half of 1 per centum or more of alcohol by volume . . .” Before the Eighteenth Amendment was enacted, many producers of fermented beverages like wine and beer, thought their products would be precluded from the Amendment and that the Amendment would only restrict alcoholic beverages with higher alcohol per volume, such as distilled spirits (hard liquor). During the push for the ratification of the Eighteenth Amendment, congressmen and the media particularly focused on the more “evil” and most alcoholic distilled spirits, thus allowing producers of wine and beer to believe they might not only evade the financial misfortunes of the Eighteenth Amendment but also flourish from the elimination of the distilled spirits market share. With the addition of the Volstead Act, however, these beliefs became misguided; Title I includes wine and beer under its definition of “intoxicating liquors,” as both wine and beer contain more than .5% alcohol by volume.

What are the exceptions of the Act?

Despite the restrictive measures of the Volstead Act, it allows for some deviations from its control. Section 3 of Title II reads, “[l]iquor for non beverage purposes and wine or sacramental purposes may be manufactured, purchased, sold, bartered transported, imported, exported, delivered, furnished and possessed, but only as herein provided . . .” Additionally, section 6 of Title II reads, “a person may, without a permit, purchase and use liquor for medicinal purposes when prescribed by a physician . . . and except that any person who in the opinion of the commissioner is conducting a bona fide hospital or sanitarium engaged in the treatment of persons suffering from alcoholism, may . . . purchase and use . . . liquor . . .” Additional exceptions include the use of alcohol for “non-beverage” purposes (i.e. industrial use), such as for paints, chemicals, in manufacturing other products, etc.

NOTE: The Eighteenth Amendment was repealed by the ratification of the Twenty-First Amendment in 1933. The National Prohibition Act, or the Volstead Act, is—to this day—unconstitutional.

(Image Credit: The 18th Amendment and Greenwich Village History, respectively.)

For more information on wine or alcohol law, direct shipping, or three-tier distribution, please contact Lindsey Zahn.

DISCLAIMER: This blog post is for general information purposes only, is not intended to constitute legal advice, and no attorney-client relationship results. Please consult your own attorney for legal advice.